March 2023 at the Gallery

Volume 14, Issue 3

Featured Artist:

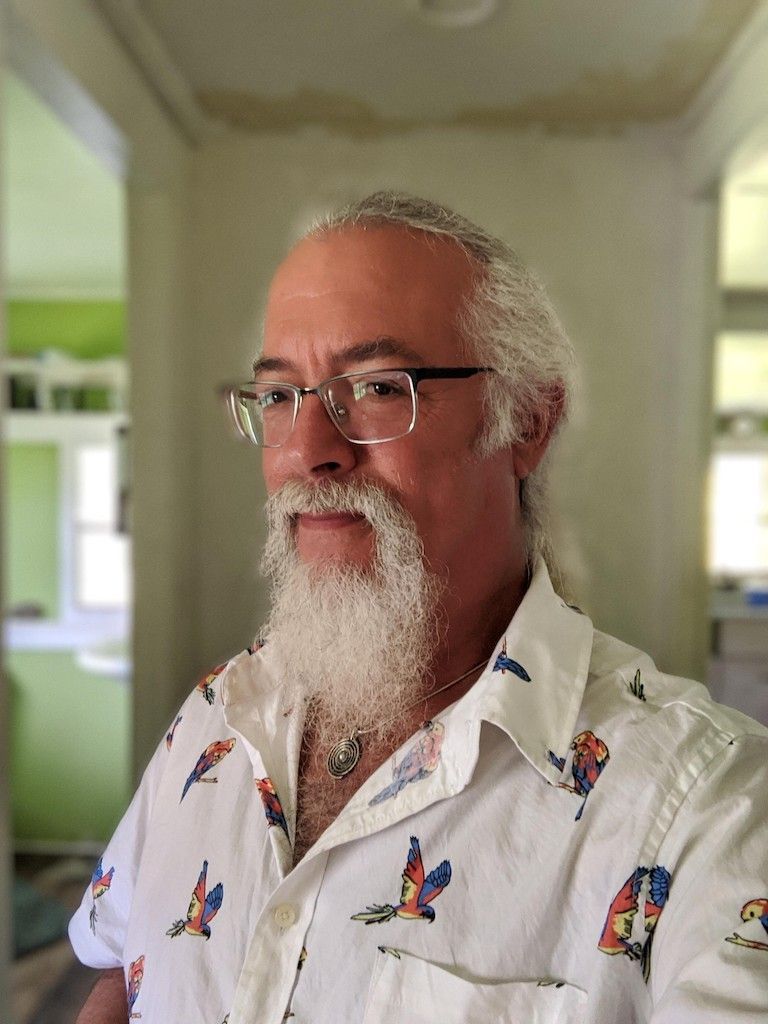

Shannon Nakaya

As much as I enjoy learning from and writing about others, I have a hard time writing about myself, especially in a way that might be inspiring to others. Realizing my upcoming turn as featured artist, I approached Newsletter Co-Editor Tamisha Lee about interviewing me like any other subject and writing this article. So here it is. I am so happy I asked and grateful that she accepted. If this article fails to interest, it is a discrepancy between the artist and the reader; the writing is true.

Shannon Nakaya vibrates with bird-like energy and self-deprecating laugher as she chats about her work in her studio. Her eyes sparkle and her hands flutter as she describes how she discovered origami and how it has challenged her notions of art and design.

Shannon started folding around 2011 when she discovered "extreme" origami - very complex structures with 200-300 steps, creating complex, expressive objects. Shannon then did a deep dive of research, buying books, watching videos and teaching herself about this intriguing practice.

In part, her research was driven by her desire to make an origami version of her beloved corgis. But she could not find a appealing pattern. Not finding a pattern to follow sent her ricocheting off in a completely new direction: designing her own origami patterns. She says designing opened up completely different pathways in her brain. Up until this point, her folding practice was mostly about following directions created by others. Folding using a pattern is about precisely following directions written by someone else. Follow the path and end up with the form intended. Not much thinking or creativity involved. But designing, designing was about engineering, creative thinking, and figuring it out. Why use this fold? Is it structural? What does it do for the form? Will doing it a different way bear a better result? Designing wasn’t about being obedient to a set of directions, but about creative problem solving. This was about leading, tearing off in a new direction, not about following a set of prescribed steps. This was not about blind obedience, this was about creation, engineering, and math! A totally new path, personally and artistically. Now she could spend her time creating exactly what she wanted and not following directions from someone else!

Shannon works only in creatures. She wants her creatures to tell a story, to move, to express their personality. But it is also important to Shannon that creatures are anatomically correct, that they look like what they represent. A manta ray should look like a manta ray! Another way she finds inspiration, creating more and more realism in her pieces.

Most of her origami dogs these days are commissioned pieces of beloved pets. Through photos and stories and becoming acquainted with the animal, she aims to capture not just their physical traits, but also to instill a bit of their character and personality within the folds.

Art Journeys With Shannon Nakaya:

Origami Reversion

Mirriam-Webster defines reversion as "an act or instance of turning the opposite way." So while origami is often about folding paper to represent an object, Origami Reversion would be about reconstructing the object from the origami. It's kind of like how archeologists create dinosaur models from old bones.

I'm making this up, by the way. But it's what I've been exploring in my studio these past months, and having too much fun with it not to share. I started with an origami giraffe folded from a 9 foot x 9 foot square. I forgot to photograph it, but it looked pretty much like this floppy giraffe. At 5-1/2 feet tall, it would never stand on its own.

I added some masking tape to hold it together, some metal tubes to help it stand, and some stuffing to flesh it out. After that, I needed to make it sturdier, so I layered on an exoskeleton using fiberglass casting tape, essentially creating a reasonably sturdy armature or framework for a sculpture.

Then I added cement. Actually, I did this several times as I learned about cement, mortar, concrete and differences in hardness, drying times, texture, etc. I also knocked it over, broke it, patched it, broke it again, patched it again, decided it wasn't going to work, and tried with a different material. It really was an Art Journey. Eventually I landed upon the right formula for the project and ended up with something that was stronger and sturdier and more stable.

Finally, I added some color and voila! Something resembling a giraffe based on an origami!

Shannon Nakaya, continued

Shannon often enjoys working large, creating pieces that are six or seven feet tall or long. To do this, she has to work with large sheets, as large as 4 feet wide and 27 feet long to create the seven foot long aerial dragon that hangs above the gallery entrance. Often, with large pieces, Shannon is forced to work on the floor of her studio, crawling around to make the longer folds. As the piece progresses, she is then able to roll up sections of the paper, allowing her to work on a table (yay!) and focus on specific areas.

Shannon has a repertoire of different folds that she uses and combines to create her creatures. Many animals start with a base form with a mathematically determined number of points. Each point will become a body part: head, legs, tail, or other parts.

Other creatures, like her large dragons and mo’o (lizards) and menehune are designed from a technique called box pleating. To make these, Shannon makes accordion folds in one direction, and then does the same perpendicular to the first folds, and then again diagonally. This allows Shannon to expand certain areas and contract others, creating shape. It also allows her to create scales, which adds texture. Creating a library of different folds, almost a language of folds, is what creates the personality and unique nature of each piece. Creating a head or face using a particular set of folds allows her to sculpt a range of facial expressions. Similarly with folding a body and sculpting it into different positions. In this way, she is able to give life to her pieces.

Most of Shannon's origami pieces are folded from a hand-dyed, water-proof paper to lend even greater variation to the heirloom-quality pieces that she can create. Still, paper alone can hold only so much shape and support only so much weight. So Shannon uses hidden wires and glue to hold the shape and personality of her pieces. Shannon has also been playing around with creating concrete sculptures with an internal origami structure. This allows her pieces to grow even larger, but consequently quite heavy as well. We cannot wait to see what comes out of Shannon’s extremely fertile studio next!

Shannon will be at Kailua Village Artists’ Gallery on Friday, March 10, 17, and 24.